Hexcrawl Checklist: Part One

You want to run a player-driven hexcrawl campaign. A well-made hexcrawl nearly runs itself as the players are in the driver’s seat for what to do next. But a lot of work goes into making a hexcrawl that facilitates player-directed exploration. As my colleague, Ava Islam of the Permanent Cranial Damage blog, recently explained, a hexcrawl can facilitate both aimless exploration and focused, directed travel without having to switch between systems, but that a good hexcrawl depends on a well-designed hex map. What do I mean by a good hexcrawl? I mean a game involving wilderness exploration (using hexes) where the players have sufficient information to make impactful choices about where their characters will go next. The purpose of this post is to provide comprehensive guidance for creating your own hexcrawl. Ava’s post was more dialectic, engaging in a conversation about hexcrawls and pointcrawls, but this post aims to be more didactic, giving you advice on how to accomplish the satisfying synthesis Ava posits.

I can’t write a post about outdoor exploration campaigns without talking about the West Marches. In the unlikely event that you have stumbled upon this humblest of blogs but aren’t already acquainted with a West Marches campaign, I will briefly entice you with a description. The “West Marches” was a campaign Ben Robbins, the creator of Microscope and other games, ran between 2001 and 2003 and wrote about on his blog on October 17, 2007 (15 years ago today). It got another boost of notoriety when Matthew Colville posted a video on it about 5 years ago and is now one of the most popular “style” of D&D campaigns being run online. A West Marches campaign is a game set in a frontier region where players are expected to explore at their own discretion. As Justin Alexander of The Alexandrian blog states, “[t]he hexcrawl structure is designed for exploration, and is really only appropriate if you expect the PCs to be constantly re-engaging with the same region,” which is exactly the premise of the West Marches. While the West Marches is not necessarily a hexcrawl campaign, a hexcrawl is probably the easiest tool you can use to bring the promises of a West Marches game to your table.

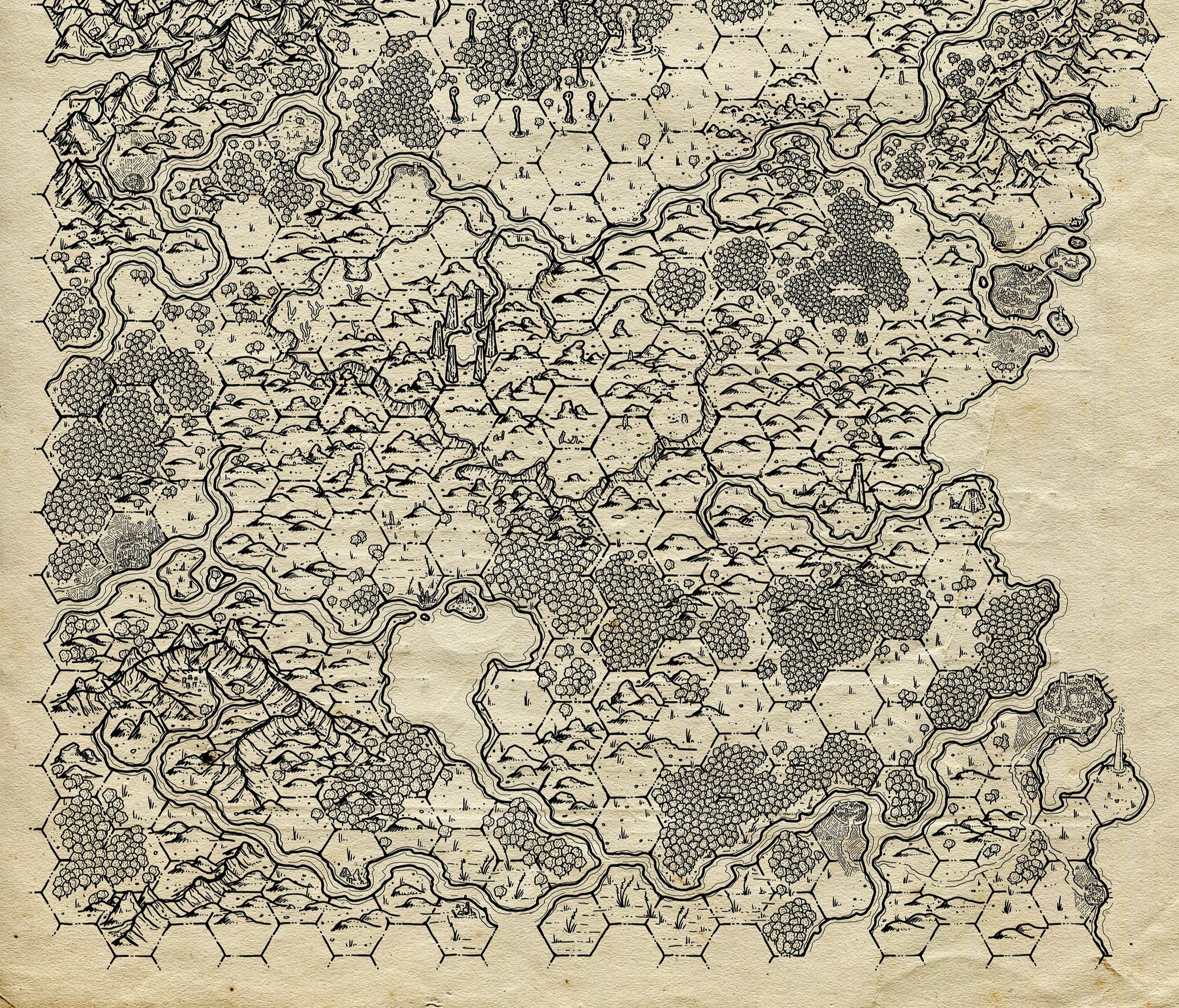

A hexcrawl is only as good as its hexmap. In the aforementioned post from Ava, a bad hexmap can lead to “aimless, pathless wandering where one exit is as good as the other”, while a good map can drive its own narratives. She describes the Dolmenwood campaign map as “one of the best designed hex maps [she’s] seen,” because of the following features:

“at a glance we have roads of differing qualities, bodies of water (combined with elevation for differences in upriver vs downriver), landmarks visible on the horizon, towns and settlements, and different terrain types making up distinct regions of the map. This is not even getting into the stuff that isn't apparent, like the various overlapping territories of political control by various factions, the differing monster ecologies between regions, the various magical effects of the ley lines criss-crossing the wood etc. which the party pieces together from rumours, intelligence, and experience and mark up on their map.”

This post sets out to do give you everything you need to (1) run a hexcrawl and (2) make a good hexmap for your hexcrawl. In a future post, I may also apply this advice and make an example hexmap (and if you are from the future, that post is already written and you can read it here [currently not the future, no link is provided]). Unlike my previous Encounter Checklist, the best hexcrawls have each of these components (perhaps with the exception of the subhexcrawl, but more on that later). Each of these points could be their own complete series of blog posts, so I am going to try keeping it short and sweet for each section and include links to further reading for each section. I don’t know why I said “try”, by the time you are reading this I already did this, or I forgot to delete this promise that I would.

#1: Hexcrawling Rules

A hexmap alone does not a hexcrawl make. You need rules that govern how the players interact with the map. There are so many D&Dish systems out there and they all handle overland travel somewhat differently, but at a baseline, your hexcrawl rules should cover the following concepts:

The travel modifiers Ava Islam uses for her ongoing hexcrawl campaign, expressed for her system, Errant.

Variable Movement: This encompasses both the travel speeds of the characters (how fast do they go on foot versus horseback versus a 1912 Stutz Bearcat) and how their movement is impacted by the terrain (it is faster to walk along a road through a pleasant meadow that to trek through a swamp). These rules are absolutely key to making a hexcrawl an engaging mode of play where players have to determine what the best route to take is (though there are other considerations, such as whether the quickest route takes them into the territory of an enemy faction, per the example in Ava’s blog post).

Time & Risk: It does not matter whether it is faster to walk through a meadow or a swamp if time does not matter in your game. The best way to do this works in tandem with variable movement: use turns. Each turn, the players can move as far as the rules allow, and there is also a chance of a random encounter or their supplies running out or something else happening to them. The best way to model this is the Hazard System (i.e., overloaded encounter die) from Necropraxis, or its descendant in games such as Errant (now in print!) by the frequently aforementioned Ava Islam. Using this rule (or procedure) slots all the pieces perfectly. However, this isn’t the only way to represent time pressure in a hexcrawl. On a more macro-level there is changing weather, changing seasons and time-specific events. If the characters don’t arrive at the city of Threshold before the Demon Princess’ coronation, it will all be for naught! I will talk more about both random encounters and other ways to make time matter in #s 6 and 7 (respectively) of this checklist.

Travel Actions: Players are not always on the move in a hexcrawl. Sometimes they are cooking, resting, scouting, etc. Your travel rules should have some way of differentiating these. Because the best hexcrawl rules are turn-based, the rules should give some guidance for what happens when they take whatever action they describe during that turn, be it moving to a new hex, climbing a landmark to get a better view of adjacent hexes, or hunting, cooking and eating an owlbear followed by a food-induced rest (all of that’s probably going to take a few turns…).

Getting Lost: Imagine combat rules without a chance of death. That is what travel is like without a chance of getting lost. The rules for getting lost should have three elements: (1) stuff the player-characters can do to avoid getting lost, (2) the consequences of being lost, and (3) getting unlost. For (1), being in a familiar location, traveling along a road, river or treeline or similar things should totally obviate the need to check if the characters get lost, and even outside of those situations it may be easier to get lost in a swamp than in a meadow. For (2), there are lots of ways to make it a pain in the ass to be lost in the wilderness. The way I tentatively endorse is taking away their map. If that doesn’t feel punitive enough, you could also add a random chance of them veering from their intended destination. For (3), I take a page from Caves of Qud and say that the player-characters get unlost when they come across a familiar landmark or a person they can ask for directions.

Sleep & Starvation: These rules add additional risk and reward to the hexcrawl. The characters need to eat and sleep regularly. If they fail to, there should be undesirable consequences. But there may be reasons why the players might decide to pack less rations or press on during nightfall. The consequences make these choices more meaningful, even if they are never triggered. I always suggest somewhat draconian starvation rules not simply due to adherence to realism (though it does probably suck to wander the desert with no food or water) but because the mere presence of the consequence exerts an invisible weight on the player’s choices. As another colleague, Jay Dragon of Possum Creek Games, points out “[g]ame mechanics shape the game played at the table, even when they’re not actually used during the game.” Suddenly you have players who care a great deal about what they carry. “Do we really need this extra lantern when we could carry an extra week’s rations instead?” Of course, you also need encumbrance rules, some limit on how much stuff player-characters carry to make almost any game involving exploration meaningful. But you already knew that; we all read Gus L. (“Encumbrance rules are close to necessary for Classic Dungeon Crawl play, because they control player access to supplies, and also determine how much treasure the party can obtain in a single expedition”) here on the Prismatic Wasteland, right?

Further Reading: Solipsistic Hexes, A Procedure for Exploring the Wilderness, In Search of Better Travel Rules, Fast Travel & Watch-Keeping Procedure, Hexcrawling Procedures: a Simple Guide

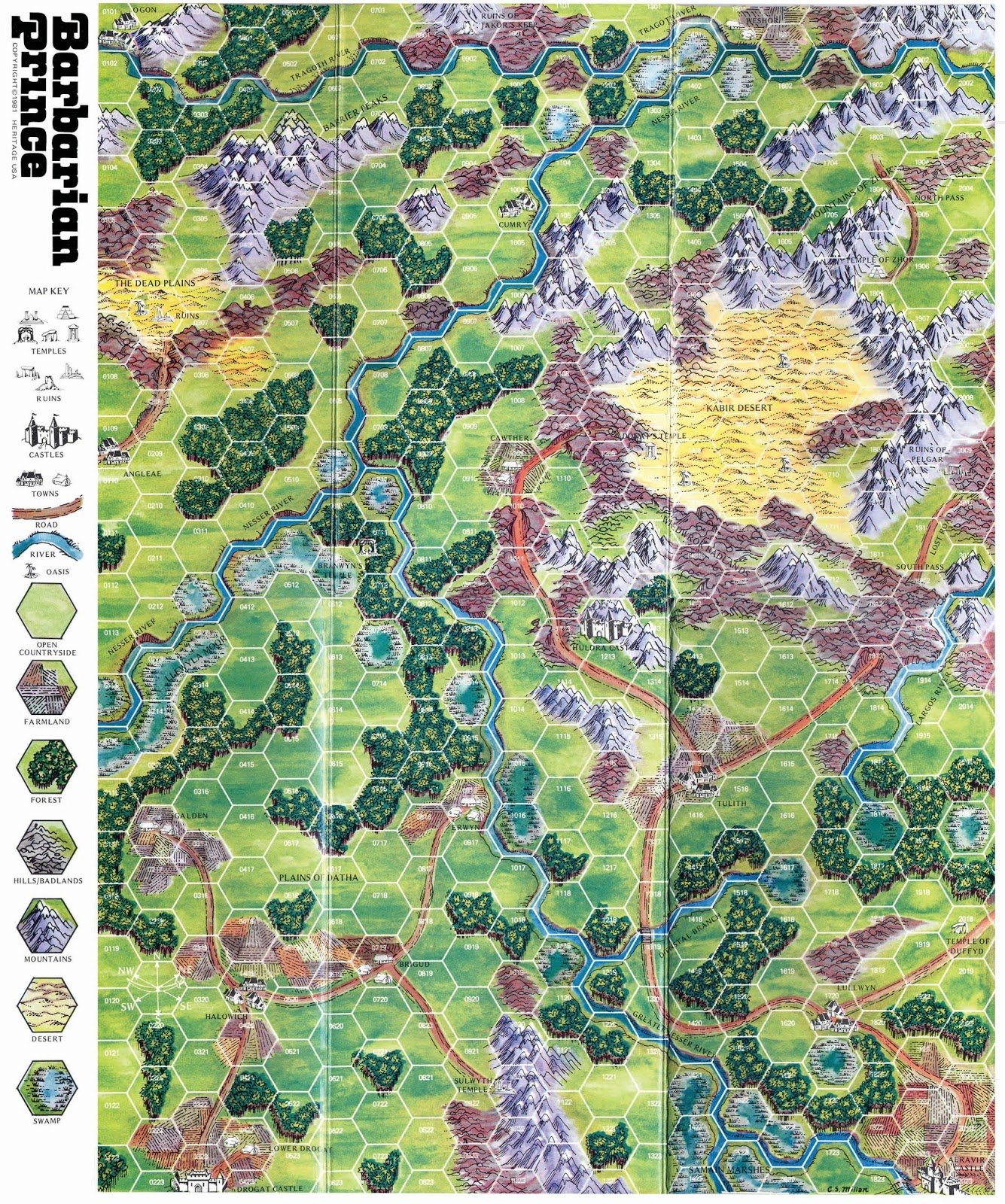

#2: Hex Terrain

This is the most “Step 2. Drawl the Owl” section of this so-called checklist, but it is so because there are so many different ways to skin this proverbial cat. And all the advice wouldn’t really fit in a single blogpost even if it were the sole topic (see, e.g., Trollsmyth’s 20-part series on the topic or Bat in the Attic’s 22-part series, both of which are replete with excellent advice). Also if you want a nice and pretty hexmap, you may want to check out the hex kit tool (reviewed by Ben Milton of Questing Beast fame here). Also, it is generally accepted common wisdom within the OSR playstyle that hexes are generally 6 miles across, but recently Joel of the Silverarm Press blog made a compelling case for a 3 mile hex, which improves the ability of players to make informed decision about their travel and also better comports with pseudo-medieval settings, not taking into account our modern conceptions of distance, warped as they are by our cars and trains and space shuttles.

There are also as many methods to make a hexmap as there are hexmaps. These range from the incredibly detailed method from Rob Conley of Bat in the Attic, which explain how ocean currents and networks of drainage basins work (it is all quite interesting, if a bit much) to the method outlined by Justin Alexander, which boils down to “throw down some roads and rivers”.

I don’t (yet) have a method I use every time when making a hexmap. I’m a fucking hexmap artist, each hexmap is a unique work of art. But my quick and dirty guidance is a bit of a synthesis from my portrayal of the two approaches above. When creating a hexmap, you should strive for logical placement of features. Internal consistency provides a sense of “realism” and, more importantly, helps players be able to make informed decisions. Update: “Fantasy Map Making Geography 101” includes excellent general advice for building a realistic world, with approachable discussions of how to simulate plate tectonics, determining where certain landforms tend to be, discussions of climate and weather, etc. while keeping in mind the fantastical frame D&D type games tend to have.

A: Draw some mountains (or hills) and maybe a coastline (or lakes). These are the most important features and are going to help you decide where to put the other stuff. If you drew a lake, they usually don’t form too far away from your elevated hexes like the coast might (which should be toward the edge of your map, classic fantasy map style). If you drew a mountain, some of the hexes surrounding the mountain might be hills.

B: Draw some rivers. These should all flow from the elevated hexes you drew down to the lakes or coastlines. If there are no lakes or coastlines, maybe they flow off the map. (Generally, I make rivers run along the boundaries between hexes while I draw roads running through hexes. The reason is because rivers most often serve as impediments to crossing between hexes [i.e., you need to find a bridge or boat or swim across] whereas roads speed you along your way).

C: Draw some forests. Dot down some patches of forest, woods or other vegetation. I tend to place mine near the mountains and toward the north end of the map, but you do you.

D: Draw some badlands, deserts or wetlands. A regional map does not (and often should not) have all of these hex types but a few are always nice. Wetlands are usually coastal, whereas deserts and badlands tend to be on the non-ocean side of mountains. Are you a geologist who knows that I am a fraud and that my advice makes no sense? Comment down below!

E: (Optional) Name your regions. This is just fun. If you have clusters of hexes that are roughly the same hex type (there may be a couple stragglers within the cluster, but you can tell if it’s still a cluster), then that is a region. Give it a fun two-word name. Below are some of the region names from the original West Marches. Even these simple region names get my imagination going, as a player. These are also useful when we get to the random encounters, factions and rumors steps (#6, #8 and #9, respectively).

“The whole territory is (by necessity) very detailed. The landscape is broken up into a variety of regions (Frog Marshes, Cradle Wood, Pike Hollow, etc.) each with its own particular tone, ecology and hazards. There are dungeons, ruins, and caves all over the place, some big and many small. Some are known landmarks (everbody knows where the Sunken Fort is), some are rumored but their exact location is unknown (the Hall of Kings is said to be somewhere in Cradle Wood) and others are completely unknown and only discovered by exploring (search the spider-infested woods and you find the Spider Mound nest).”

F: Draw some settlements. Place the city (or largest settlement on the map) in the most geographically desirable location. If you’ve played Civilization, you should have a good enough grasp, but if not, it should be near water of some sort (typically a river). Being on a hill and having plains or farmland nearby (easy enough, if it is on a river) are also pluses. Then place 1d6 towns on the map, each near (let’s say 1d6 hexes away) the city you added, in somewhat desirable locales as well. Then add 2d6 villages, dotting the landscape. Adjust these guidelines to taste, but this is a fairly populated region. If you want an apocalyptically underpopulated region, my former colleague G. Gygax has a random table for you in his AD&D DMG. “Where are the hamlets and thorps?” you might ask if you are annoying. There’re there but not really important enough to put on the map. Same with single dwellings. It’s a fun surprise to happen across a little hamlet or cabin in the woods, but not everything needs to be on the map.

G: Draw some roads. Roads connect your settlements (and the settlements that are off the map, just out of frame, laughing too). Typically bigger settlements have nicer and better patrolled roads (patrols are important, and we are going to talk about them soon). There is a major road between any two cities (if you are following my advice exactly, the other city is somewhere off the map). If you can draw a sorta straightish line through a city and any two or more towns, then make that a major road. Otherwise, it is a minor road. If you can draw a sorta straightish line through a city and any two or more towns and villages, then make it a minor road. Nearby towns that make sense to be connected and aren’t already might be connected by a minor road. Otherwise, draw all roads that make sense but these are just trails. Put at least one trail going through one of your forests. Spooky huh?

Further Reading: In Praise of the 6 Mile Hex, Hex-based Campaign Design, How to Make a Fantasy Sandbox, Types of Terrain on Hex Maps, Making Rivers on Hex Maps, One Hundred Wilderness Hexes, Hexcrawl Addendum: Designing the Hexcrawl, Down With The 6 Mile Hex!, Fantasy Map Making Geography 101,

#3: Hex Connections

Obviously, each hex is connected to six adjacent hexes. But to make the decision to go to one adjacent hex and not another, players need some information about how the hexes connect. This is similar to the dungeon design advice that hallways, doors and other connections between dungeon rooms should provide at least some information about what might be on the next room. As my colleague, Anne Hunter of the DIY & Dragons blog, summarizes the issue, “With no information to base their decision on, they might as well roll the dice to decide which way to go. They might as well be in a straight railroad.”

The easiest way to give players information about the connecting hexes is just give them the map. The map is not the territory, of course, and does not contain every piece of information and may be imperfect, but it can make sense diegetically for the player-characters to have access to that type of information. This also works well with my advice of taking away the map when they are lost to simulate losing one’s bearings in the wilderness. Nothing makes the players realize how important information is than when they are temporarily stripped of it. Even just knowing the type of terrain or presence of roads or rivers in adjacent hexes can allow players to make informed choices because, with the rules for variable movement plus the rules for time & risks, they will be incentivized to go in one direction rather than another to get to their destination quicker.

A map showing the adjacent hexes isn’t the only way to give players information about adjacent hexes. You also have the important tools of rumors (e.g., they might have heard what might be in a new hex they haven’t explored yet), which I will discuss in #9 below. There are also landmarks. Each hex should have at least one landmark (discussed more shortly at #4) that is visible from adjacent hexes if viewed from a height. So if players want more information before deciding which way to go, they can try to find something to climb (or fly up if they have the means) to spot the adjacent landmarks. This may feel a bit video-gamey because there are so many modern open world games where you climb something to unlock a regional map, but it is also just how this stuff works in real life. If you don’t believe me, climb on top of your roof and learn a bit more about your neighbors. I just tried this and learned that Chris from next door is into kayaking. Neato!

Further Reading: Hexcrawl Addendum: Connecting Your Hexes, The Wilderness is a Dungeon: Jaquaysing Your RPG Sandbox, Hexcrawls ARE Pathcrawls, The Ring Map Layout

#4: Key Hexes

It ain’t easy making a hexmap. Turning once more to Mr. Alexander, he notes that a “key principle is that every hex is keyed” and, as a consequence, “[t]he prep for a hexcrawl is frontloaded.” I find a framework is helpful in guiding my prep, and the gold standard framework for keying hexes is the “Landmark, Hidden, Secret” classification from Anne of DIY & Dragons. As a brief aside, while overland maps is the most obvious application, this is a useful mental framework for nearly anything (for instance, my colleague Ty Pitre of the Mindstorm blog applied it to monsters for a fascinating method to make fighting monsters an engaging puzzle). Landmark, Hidden, Secret is as an important maxim for old-school inspired design as Chris McDowall’s Information Choice Impact doctrine (which implicitly is also at the core of much of my advice about hexcrawl campaigns).

Landmark information is automatic and free. Anne again: “Players hear landmark information the first time without asking, and if they ask, they can be reminded of it as freely as they heard it at first. Learning landmark information doesn't take up any fictional time and doesn't pose any risks.” This means that, as soon as the characters enter the hex, the referee will tell them about the landmark feature and they don’t need to spend a turn exploring the hex to find it out. A landmark feature in a hexcrawl is a large, obvious feature of the hex. As my colleague, Ben L. of the Mazirian’s Garden blog describes them, “[l]andmarks are the anchors of exploration. They generally represent easily identifiable terrain features that allow one to locate oneself clearly on the map.” Landmark features might be a ruined castle on a hill, a spaceship crashed into a mountainside, a volcano, a temple half-buried in the shifting sands, a settlement (village or larger; sorry again, hamlets), or a massive tree looming over the rest of the forest. If a hex doesn’t have an obvious landmark like this, then the landmark feature is simply the dominant terrain type of the hex. Usually if you can give a hex a specific name, it is named after its landmark feature.

Hidden information is earned by asking for it and accruing some cost (i.e., time & risks). Because we already have time and risk built into the hexcrawl, this is simple to adjudicate: when the players choose to spend a turn searching or exploring a single hex, they automatically learn about the hidden landmarks in the hex. This takes time and might trigger a random encounter, but otherwise, it is automatic once they pay that cost. Hidden features of a hex are things that aren’t immediately obvious as soon as they enter the hex but are relatively easy to notice once they start poking around the area. It could be an ogre’s shack in a swamp, a series of small caves in a hillside, a collection of steadings masquerading as civilization (that’s right, it’s finally a hamlet), or a treehouse containing diminutive cookie-baking elves. Dungeon entrances are most often hidden landmarks, although more ostentatious dungeons may have landmark features that are their entrances. If the dungeon is large enough to have multiple entrances (which is best practice), maybe there is an obvious landmark feature entrance but a hidden feature entrance that is perhaps a more beneficial, less well-guarded way to sneak into a lower level of a dungeon. Take the castle on the hill landmark feature as an example: perhaps entering through the castle directly is the obvious entrance, but that entrance is guarded by the bandits that have made the castle their base of operations. But there is a hidden feature that is an old well. Descending down that well takes you directly to the basement level of the dungeon, allowing clever players to take the bandits by surprise.

Secret information is never guaranteed but always costly. As Anne explains, secret information might be secret because there is simply not enough time to find it (“A methodical all-day search might be certain to turn up what you're looking for - but to uncover it in a single, 10 minute exploration turn requires luck or insight or skill.”) or because certain skill is required, a special knowledge that not everyone possesses and which has a chance of failure. In the hexcrawl context, I typically attach a secret feature to a landmark or hidden feature. For instance, maybe spelunking the right cave entrance in a network will lead to the cave city that is only reached by the network of secret cave entrances. Or maybe the massive tree has subtle elven runes carved into the base and translating them reveals a “speak friend and enter” type puzzle that will open a secret door in the tree itself. So I just describe the landmark or hidden feature and, if the players decide to investigate further, bring out the dice. Another way to conceptualize secret information in a hexcrawl is that the secret information are the dungeons themselves. Exploring a dungeon takes more than a single die roll, but the framework is unchanged: dungeon exploration is uncertain and costly.

Nearly every hex should have a landmark feature, most hexes should have a hidden feature (or multiple), and a few hexes should have a secret feature. I asked Anne if every hex should contain a hidden feature, and she said it is better to start with just one hidden feature and not in every hex (suggesting maybe 4-in-6 hexes having a hidden feature). Her reasoning was that this better encouraged exploration across the hex map rather than meticulously digging deeper into every single hex. Hexes without hidden features serve a similar purpose as empty rooms in dungeons. It increases tension and keeps players exploring. Gambling is fun.

Further Reading: Landmark, Hidden, Secret (required reading), Using Landmarks in Wilderness Travel, Designing the Hexcrawl - Part 2: Stocking Your Hexes

#5: The Subhexcrawl

Subhexcrawling is more trouble than it is worth. This is more of an anti-checklist item: you do not need a subhexcrawl for wilderness exploration. I think different modes of play as being zoomed-in to the level of abstraction most appropriate for the type of action being performed. It gets messy if you use the hexcrawl procedure on 6-mile hexes and then zoom-in and use the same procedure for exploring 1-mile hexes. The above-described method of just taking a turn to abstractly say that the characters are spending a turn exploring a hex is all you need, rather than zooming in to increasingly granular hexcrawls-within-hexcrawls. Exploring hex features, such as dungeons or settlements, do zoom in and use whatever procedure is most appropriate for that location. Similarly, if there is a random encounter, you zoom in even further and run the encounter outside of the hexcrawl procedure entirely. Ben L. correctly identified another issue that subhexcrawling “makes the construction of the map a daunting task. I now need to not only assign a type to the hex, and stock it with features, but construct sub-hexes with detailed topography and geography that allow me to locate those features in the hex. This basically ensures that I will never be able to prep a sizable map.”

Why would you ever worry about traveling within a hex? In a comment on my colleague Dwiz’s blog, Knight at the Opera, Anne posited that “there are only two reasons to worry about traveling inside a hex. The first is if the hex contains an outdoor adventure site, akin to an open-air dungeon. In that case, as you note, the solution is to zoom in to a smaller scale map of that adventure site. The second reason to worry about traveling inside a hex is because you've made your hexmap at the wrong scale and need to either make a new one or rethink your travel rules.” Both of these seem to support my conclusion: you might zoom in for an adventure site, but if the 6-mile hex is too big for your purposes, the solution is to switch to a smaller hex size in all instances, not to use multiple hex sizes at once and switching between them. However, it is my experience that thee 6-mile hex is just fine for the level of abstraction that overland travel typically takes place in.

Further Reading: Just Three Hexes, Sub-Hex Crawling Mechanics, Determining What PCs Find When They Search Hexes, How Do You Handle the “Inside” of a Hex, The Things We Find Along The Way – Filling The Gaps In A Hexcrawl or Pointcrawl

Tune in Next Time!

In the next post in this series, I will cover #6: Random Encounter Tables, #7: Calendars & Forecasts, #8: Factions, #9: History & Rumors, as well as a brief digression on the Hexcrawl-Pointcrawl Combo 3000, a method for combining the two most popular methods for running overland travel. There is a lot of meaty advice for making the hexcrawl a fully realized organic tool that can facilitate years of adventuring. I will then cap off this series with a third post where I taste my own medicine and design an example hexcrawl using the checklist steps I lay out. If you want to get emails when I post new blog posts, you can subscribe below. Otherwise, just keep your antennae tuned to the Prismatic Wasteland to hear the action-packed conclusion of this checklist.