A Better Approach to Deadly Games

If you want frequent player-character death in your games, it is less important to make it easy to die than it is to make it easy to live again. A stated design preference in OSR and Post-OSR (“POSR”) spaces is that death comes for us all, unless thwarted by clever play. Principia Apocrypha, which is a useful primer in old-school stylings, emphasizes that combat is neither balanced nor fair. Similarly, according to Gus L’s post on preserving the core nexus of classic-style play, combat is a lethal and inevitable fail state. However, the trope of the sadistic referee furnishing and refurbishing their deathtrap dungeon with dangerous monsters and devious traps is a hackneyed one. For one, it violates another principle of OSR- and POSR-style play, that the referee is not an antagonist to the other players. More importantly, it is ineffective at actually making the game deadlier. By itself, it is merely an aesthetic choice without the intended function.

“I live, I die, I live again. ”

Death Pact: Communication & Systems

Deadlier games require buy-in; buy-in requires conversation. This is true for games of any type or tone. If you want to play in a particular setting or with a particular tone, you must first bring it up with the other players. They are your collaborators and without their buy-in, you will struggle to maintain whatever consistency you desire. If you want the game to be deadly, i.e., involving character death, bring it up early. If that sounds fun to everyone, please proceed with the rest of this advice! If it doesn’t, continue to discuss and align your goals with the other players at your table. P/OSR’s proclivity for character death is by no means a truth universally acknowledged. To the contrary, the popular playstyle often deemed “modern” but more accurately denoted as OC or Neo-trad puts greater emphasis on characters as aspirational figures with their own character arcs. Players intent on such a game would be left wanting if the avatar of their hopes and dreams is brought down by a goblin’s stray arrow (for more on this and other cultures of play, including the OSR, check out this excellent article on Six Cultures of Play from the Retired Adventurer).

Quick character creation is the most effective method for producing a deadly game. The “system matters” conversation is a thoroughly poisoned well, but it is true that both systems and adventures have incentives that shape play. While XP is easy to spot, incentives (and their cousin, disincentives) can assume a multitude of forms. An interconnected web of incentives will form in any game, no matter how much we wail and gnash our teeth at such tomfoolery. But what behaviors do deadly monsters and traps incentivize? In the players, it incentivizes caution, clever thinking and combat avoidance. This is great, but not directly related to making games “deadly.” In referees, deadly level design, all else being equal, might incentivize taking it easy on the players. Both players and referees are incentivized to avoid death in any system where character creation is an involved process. If a single death brings the session, or even the campaign, to a screeching halt, rules will be bent and rolls will be fudged in service of keeping the game on a glide path. But if character generation is quick (typically this means random), the deadliness of the dungeon’s denizens may be fully realized.

No Time to Die: Funnels

In a funnel adventure, death lurks around every corner. Coined and popularized by Dungeon Crawl Classics, a funnel adventure is where each player begins with a handful of low-level (typically level 0) characters. Through a process of attrition, only a band of bedraggled survivors make it to the end of the adventure, and these poor, unfortunate souls then become the player-characters for the subsequent campaign.

In a funnel, death offers frictionless fun. Because character death does not necessitate generating a replacement character, death does not slow the game at all (and may even speed it up to its inevitable conclusion). While caution and clever play is always a worthy attitude, players need not be precious with their characters. Death is almost treated like a resource for players to spend; funnels treat the loss of a character the same way other games handle losing HP or using spell slots. When there is a problem in a funnel, the first step toward a solution is often to throw one of the unlucky characters at it. If they die, the survivors have at least learned something about the shape of the problem and how to overcome it. But there is no crying over the character’s spilt blood—there is more where that came from. This different set of assumptions and incentives produces a very different game, where players are more likely to react with glee than with horror at the death of their character. However, the funnel is not the game. The funnel is, at best, a tutorial for the “real game” of the ongoing campaign. But the incentives differ so greatly from said “real game” that it operates more like a mini-game, giving players a taste of what is to come and perhaps setting the stakes for the rest of the game. A funnel says “this world is truly deadly” but fails to fully keep that promise when the characters emerge from the funnel. When you emerge from that first dungeon, smeared in the blood of your former party members, the friction of death reappears as if to say “welcome to the real world.”

Generational Death: A Rasp of Sand

(Blogger’s Note: I intend to produce a review of A Rasp of Sand in toto. My comments here are merely a discussion of the innovative way that the adventure treats and incentivizes death. If you are interested in a more typical review, keep your eyes peeled at the Bones of Contention blog, a TTRPG review collective.)

A Rasp of Sand (AROS) by Dave Cox innovates on the typical dungeon crawl by pulling ideas from TTRPG-inspired video games, specifically the roguelike genre. A core feature of a roguelike game, as opposed to more common RPG video games, is permadeath. When your character dies, you must start over from the beginning with a new character. There are no save points, no bonfires to safeguard your progress. The same is true in AROS. When any party member dies, the dungeon begins to flood to expel the other adventurers. The players will return to the dungeon again but not with the same characters. Instead, they will play as the descendants of their former characters.

“In AROS your story isn’t over at your first Heir’s death or retirement. The next Heir must take up the Deep Queen’s Crown and attempt to return it. You don’t start from scratch though. When creating the next generation of Heirs, keep in mind that they were raised by the previous Heirs, or at least know of them. If they are your previous Heir’s biological children they may resemble their parents. If they are adopted then roleplay some ways that they represent your family.”

If quick character generation reduces the disincentive to die, AROS actually provides some degree of incentive to character death. The next generation has a greater likelihood to have improved abilities, inherits their predecessor’s mutations and begins with an heirloom from the previous delve. New characters also learn from their ancestor’s experiences by ingesting the dead ancestor’s “Sand” a material left behind by the dead that imparts a measure of XP and the memories of the dead creature, if not mixed with the Sand of others. The most prominent form of character advancement unlocked by death is the family trade. Each character belongs to a family, and each family specializes in one of twelve trades in the community. Each successive generation that carries on the family business gains a new trait associated with the trade. For instance, if your character were a Smith, they begin with the Repair trait, which permits repairing equipment. Their next descendant, assuming they follow in your first character’s professional footsteps, will have both the Repair trait and the Smithy trait, allowing your character to repair armor and weapons during a rest as well. After five generations of Smiths, you will be a Master Craftsman, able to craft Master-craft weapons and armor. In AROS, death is barely a setback; it propels the game forward.

“If you strike me down, I shall become more powerful than you can possibly imagine.”

A Killer Idea: Flunkies

Prismatic Wasteland is not a deadly game; or at least that isn’t a core component of its ethos. But at the same time, I wanted to avoid any hesitation the referee might have for killing a character when the circumstances (and the mechanics) warrant such a consequence. To do so, it is essential that the player, after they take a breather to mourn their character, can jump right into the game. Whitehack allows recently departed characters to stay in the game as a ghost of their former self, at least for the remainder of the session. They can no longer swing their sword but they can walk through walls. Although this is an evocative and easy solution, it does not fit the tone of Prismatic Wasteland, a whimsical post-post-apocalyptic game of science fantasy. So let’s turn to how I smooth over death, reducing friction at the table and freeing my hands to be as deadly (or not) as I want: the flunky.

David Graeber, in Bullshit Jobs, describes “flunkies” as a subset of bullshit jobs that exist to make their superiors feel superior. Basically members of one’s entourage. They serve an essentially similar function in Prismatic Wasteland. As I’ve written about previously, I generate character stats by having everyone (including the referee) generate an array of stats by rolling 3d6 in order. Then the non-referee players take turns picking those stats in snake draft order (the most recent time I did this, my players accused me of knowing about fantasy football, but I promise you that I am innocent of such charges). Because the referee also rolled an array, this process results in (a) the equivalent of a reroll for each player and (b) an extra array of stats. In my earlier post on this method, I suggested letting those stats “inform a character that exists somewhere in the Prismatic Wasteland, perhaps harboring an unspecified, cosmic grudge against the Heroes for reasons they can’t explain.” However, I have settled on having every party start out with a flunky, a character that never levels up but follows the player character on their quest, doing their biddings. The reason for this change also relates to incentives. The players are already incentivized to pick the best stats, leaving all the duds for the dummy character. But if that dummy character is an ally, a flunky who they will go on adventures with and who they may end up playing, albeit temporarily, the players have competing incentives: do I leave all the terrible stats for the flunky, or do I at least give the flunky a few middling stats? Competing incentives to make mutually exclusive choices makes the satisfying information-choice-impact doctrine all the more fruitful (but perhaps that is a topic for another day).

The flunky not only makes the players feel more competent but is also a readymade stand-in for players whose character dies. Due to the above-described process, the flunky is likely to have stats that are, to put it as charitably as possible, total garbage. And as the players level up their characters and begin to deck themselves in gear and magic items, the flunky is there to remind them how fragile they once were. But the flunky is also a quick insert when a player’s character dies. It is not a permanent solution; the player will need to make a new character. But it can wait until after the session or before the next. There does not need to be a pause in the action while the player rolls and tallies d6s. (A third effect of the flunky is that they are fairly endearing in practice. They become a sort of mascot for the group, like Scooby-Doo or Snarf.) A flunky is a useful stand-in, a panacea to the ills of character death.

Deadly games can be painless—not for the character necessarily, but for the gaming group. By reducing as much as possible the friction surrounding character death, it makes death more likely. If you want a deadly game, your time is better spent communicating these expectations to your party and tuning the dials of your system than dreaming up unsurmountable foes and deathtraps. I would not go so far as to claim that YOU CAN NOT HAVE A MEANINGFUL CAMPAIGN IF STRICT DEATH RECORDS ARE NOT KEPT, but the real possibility of character death in a game adds a dimension that is not otherwise present. I would encourage you to make death a seamless play experience.

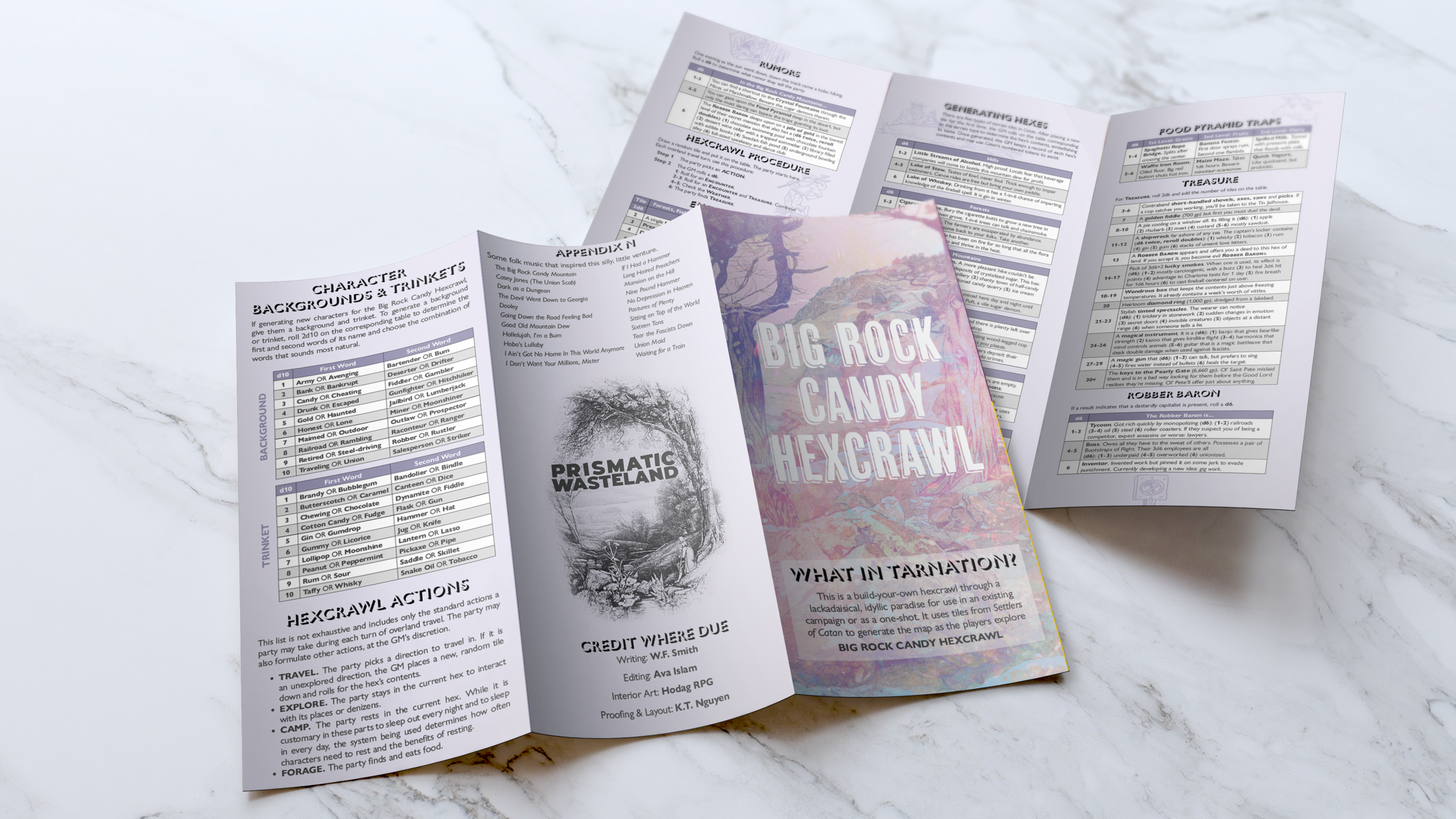

(July 12 Edit) Big Rock Candy Mountain Hexcrawl

I hope you enjoyed my thoughts on deadly games! If you are looking for a new OSR adventure, I just released my first game, Big Rock Candy Hexcrawl. This is an adventure inspired by leftist folk music from the turn of last century, but it also uses the tiles from Settlers of Catan to procedurally generate the map! It has separate pages with monster stats for Old-School Essentials, Knights of the Road and Errant, but it’s system neutral and ready to be run using your system of choice. It’s pay-what-you-want on itch.io, so I hope that you check it out!