Schrödinger’s Chat 2: Amended & Restated Quantum Language Rules

I started this blog during the death throes of the year 2020, and like most baby blogs, my web traffic was nothing impressive. In fact, my first four or five posts combined for fewer views than I received on any single day of 2023 to give you a sense of the disparity. As a consequence, some of my posts can be a tad bit obscure. But also with three years of growth, I sometimes revisit a post and decide I don’t fully cosign what I said before. This is the first of my “amended & restated” posts, where I revisit a topic to one-up my past-self. Suck it, 2020-me!

This revisitation was sparked by my colleague, Tom Van Winkle of the Lich Van Winkle blog. He presented an excellent treatise on languages (in general, but also specifically as applied to TTRPGs). One of his pieces of advice, which he suggests for players who pop into an ongoing campaign with a character that is fluent in some undefined foreign language, is to use quantum language where they can determine what that language is (and thereby what foreign lands their character is from) when they come across a speaker of that language for the first time. (Editor’s Note: and between writing this post and actually posting it, another colleague at the Blog of Forlorn Encystment wrote an also excellent treatise on languages that is full of hyperlinks to other blog posts on the subject).

This is similar to the quantum language approach I suggested in that early blog post. However, my thoughts on language have changed slightly and my rules have changed as well (inspired, in part, by the Right Honorable Van Winkle’s post). The core ideas in that post were that (1) characters don’t pick their languages at character creation before they even know what languages may be most relevant, and (2) when a character declares that there is a reason their character may know that language, the rules don’t negate that decision, they just might complicate it. If they say they know the language but fail their test, the game doesn’t say “no you don’t, Oprah”, it says “well you think you know it but you are constantly mixing up the words for “friend” with “lover” and “we seek peace” for “we wish to eat you and your kin”.

My approach remains largely unchanged, with a few tweaks. First, the test to determine whether a character knows a language is now Charisma instead of Intelligence, because (as Tom says in response to me in the comments of his post) the attribute most closely associated with "life experience" or "worldliness" should be used, which in Prismatic Wasteland is Charisma, not Intelligence. However, Intelligence still has a role to play. Prismatic Wasteland uses somewhat standard slot-based inventory rules where a character has a number of item slots equal to their Strength score. But things like spells, skills, feats, mental mutations, and–most importantly in this instance–languages take up idea slots in the character’s memory, basically a mental inventory that is based on their Intelligence score. So a Charismatic character may have been more likely to have picked up languages based on their languages, but an Intelligent character is more likely to have retained all the languages they did pick up. Obviously this lacks some of the nuance of real life, but this is also a game where characters have Intelligence scores at all. Those aren’t real, you, the person reading this, do not have some numeric measure of your platonic intelligence embedded somewhere in your source code. But we gotta abstract some things and handwave other things if we are going to pretend to be elves with just enough rigor to be fun.

Language in Prismatic Wasteland

Here are Prismatic Wasteland’s rules for language, as of now. Subject to change when I see another good blogpost, as is tradition.

Each language takes up one Idea Slot in a character’s Memory. Heroes, Sidekicks and Flunkies start with Humanitese (or another language, depending on their Haven of origin) in their Memory. They can read and write this language and speak it fluently without a detectable accent.

When a character encounters a language (audibly or in writing) for the first time in the campaign and their player has a reason to believe that the character might know that language by dent of their upbringing, education, or something else from their past, then the character makes a Charisma Test. The Test is Easy for pidgins, Moderate for trade tongues, Hard for other languages, and Extreme for dead, ancient, or unusual languages.

On a Full Success, they can read, write and speak the language with only a slight accent.

On a Mixed Success, they can speak the language well enough to convey simple ideas.

On a Failure, bubble Charisma. They believe they understand what they hear or read, but their poor fluency will inevitably lead to comedic misunderstandings or dangerous escalations.

On a Critical Success, they are incredibly erudite in this language, which may grant them Advantage when they use it, depending on the circumstances and the attitudes of the listeners.

On a Critical Failure, bubble Charisma. They badly misinterpret the meaning of grievously offend all listeners enough to cause them to react with hostility toward the Band.

Optional Technique: Simulating Limited Fluency

To simulate limited fluency in a language, require the player to only use single syllable words when their character communicates in that language. If they use any multisyllabic words, the listener responds with confusion. Similarly, the Arbiter characters speaking that language to such character should only use single syllable words.

Speak With Plants

The language of insentient plants cannot be learned by traditional means. Only Dryads are capable of producing the subtle signals to communicate verbally with plants.

Learning and Forgetting New Languages

Both of these take time, specifically downtime. Characters can use downtime to mark progress on learning a new language if they have either an instructor or are living among people who speak that language. The amount of progress needed depends on the type of language–pidgins are quick to learn but ancient languages require long, dedicated study.

But characters may also want to forget a language to clear up Idea slots in their Memory for skills, feats, spells or other languages. This also requires downtime, but specifically they have to spend a certain number of downtime turns (and the time in between downtime) not using that language. After that number of downtime turns has elapsed, their knowledge of that language will have atrophied enough that they can erase it from their Memory. If they wish to relearn it, they will have to spend downtime to reacquire those language skills, although it will be more expedited than someone picking it up for the first time.

Language in Mausritter

Another sentiment in my previous post I would like to disclaim is my disdain for the role of language in games (D&D specifically). In that post, I said “in nearly a decade of running the game, I can’t think of a time where knowing or not knowing a language caused something fun or interesting to happen in D&D”, which was true but was specific to D&D (3.5 and 5e) where I found it mostly either a bummer (e.g., a character having picked a bunch of languages at the start of the campaign and later realizing it would have been more advantageous to pick other languages in hindsight) or entirely circumvented by spells. This is similar to how most survival and exploration elements in modern D&D aren’t fun because modern D&D has so many ways to circumvent those modes of play. The ranger is just a “skip everything interesting about wilderness travel” button. Wizards are often a “skip fiddling with languages” button. But this isn’t true for all TTRPGs, and certainly isn’t true for my own games I’ve run with Prismatic Wasteland or other P/OSR systems.

One great example that comes to mind is Mausritter. Mausritter already has pretty neat language rules, though I did tweak them slightly. In Mausritter, depending on how closely related the creature is the mice, the more likely communication with the creature is. However, I think a bear should rarely, if ever, be able to speak to mice. And humans should be eldritch horrors, beyond comprehension of nearly all mice. But frogs should be able to talk to mice, albeit with archaic mannerisms. So I tweaked Mausritter’s language rules thusly:

Mice can speak to other mice easily. With other rodents, idioms may not translate. With other mice-sized creatures, can communicate in pidgin. With cat-sized or bug-sized creatures, make a WIL save. Otherwise, no communication.

Mausritter is the ideal game for teaching the OSR playstyle. Players may have become too desensitized by heroic fantasy to see dragons for the nearly insurmountable threat to the characters that they should be. Even animals are more dangerous than might be imagined by minds addled by heroic fantasy. But the danger a cat presents to a mouse is immediately understood. Similarly, players used to so-called modern games where resource management is an afterthought at best may balk at encumbrance rules. But no one bats an eye when I limit the amount of cheese a mouse can reasonably carry on their back. There is something about being a mouse in a world filled with all manner of dangerous predators like cats or hawks feels grittier, more hardscrabble than being a human in a world of dragons and giants. Accordingly, my players are extremely cautious. Fighting is always a last resort. Most of the time, they scurry from crisis to crisis, using their wiles more than their might. Language is fun in Mausritter too. I remember fondly a session with Greg and Elias Stretch where they got caught by a cat but only one of them could speak to the cat. It was absolutely chock-full of tension and comedy in equal measure, as they formed an uneasy alliance with the cat by offering to lead it back to a mouse settlement.

Coming Attractions

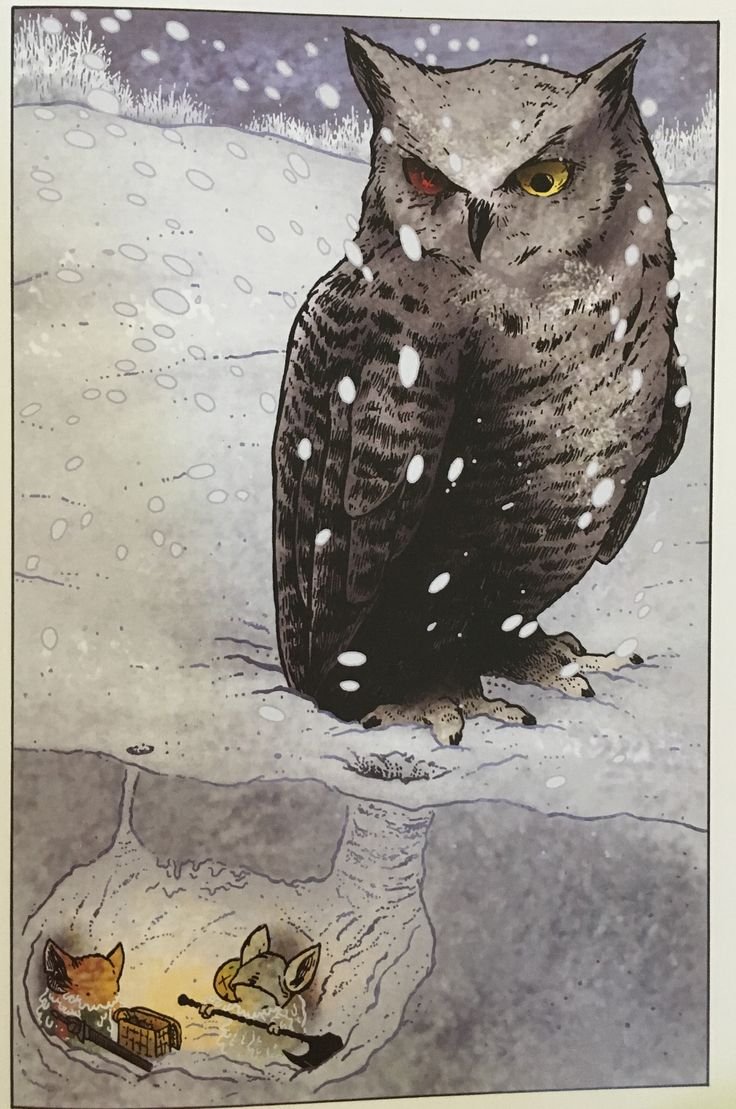

I hope 2024 will be a big year for Prismatic Wasteland! I hope to not only have more time to write, more time to design, more time to blog, I plan on releasing more full fledged games. While I work on a truly huge adventure (titled Candy County) and my whimsical post-post-apocalyptic system and setting (Prismatic Wasteland), I’m also working on some smaller releases. This cover mock-up is just a teaser of what is to come this year. If you want to keep up to date on these releases, the best way to do so is to sign up for my newsletter–you’ll get notified only when a new adventure or game is released.

A bit more detail for this teaser: the plan is two zines: one will be an Into-the-Odd based dungeon crawler where you play as Pocket Monsters who evolve instead of leveling up, which will be compatable with any ItO/Cairn adventure, and the other will be Vile Plume Mountain, an adventure for that system (but also useable with ItO/Cairn) based on the hoary classic funhouse dungeon.

I also have a Patreon if you want to see early drafts of any of my work, and just see all of my inner workings from drafts and sketches to final products.